Extraordinary scenery; heat in the 40s; no breeze until the evening; miles and miles of salt; miles and miles of sand; damp sand; dunes with scrub bushes; pebbles reaching into the horizon; looks just like you are at the seaside but the tide never comes in. This landscape was created by the red sea seeping into the depression and then the water evaporating many times; the salt is quite a big industry and it has spawned the most revolting and unsanitary of villages, where the military, local workers and phosphate companies are serviced by bars and prostitutes. Unsanitary? There is not one toilet here, and no attempt at organising any. No pits, no long drops, no attempt to harvest the human waste. You just go for a little walk on the vast flat lands, and find a flat pebble to cover up your poo. You hope someone else hasn’t found that same pebble first.

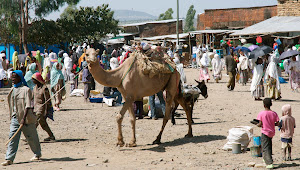

The salt is removed from its layer of sand; cut into blocks and loaded onto the camels and donkeys that wait patiently. At this point each salt block is sold for 10Birr; the Afar sell it cheap because they know that they can make a profit in other ways from the traders. By the time the camel trains have carried the salt blocks (20 to a camel; trains of about 20 camels, each with their camel master; groups of 4 or 5 trains) up the mountains to the market in Mekele, each salt block sells for 50Birr.

We visited the volcano of Irte’ale(613m); it is one of the only permanent lava lakes on the planet. Because of the heat the trek is done at night and on an evening with a full moon rising behind the summit, we started the 3 hour trek at 6pm. It was so worthwhile to be able to see the moving lava, hear that force of nature, experience the bubbling as a burst of molten rock is forced up into a splash and a burst against the sides of the crater, feel the heat, not only from the moving red lava but also from the very rock that we were standing on. This was a ‘wow’ moment; you couldn’t help but be over-awed by the sight. I shall never forget it. We camped that night on the crater’s edge and after a short sleep we trekked back down the volcano so that we were at base camp just as the sun was hitting our backs, but before the heat of the day. A lovely breakfast of pasta soup awaited us cooked by the 2 women that we had bought with us. Thank goodness that we had 4x4s to take us the 6hour drive across sands and pebbles and rocks, back to Hamd’ula and our main camp.

Our other visit was towards the North to see the sulphur pools and oily lakes of Dallol; Here again you really experience the heat of the area; it’s unrelenting and at -116m is the lowest inhabited place on earth. The colours of the sulphur lakes are best seen, so I’ll try and upload some pictures. Beautiful shapes and pools are produced and gasses can be seen escaping from the earth. The chemical is harvested from time to time and there is an old Italian settlement on a nearby ridge, now only used by temporary workers. The other lake bubbles incessantly too and here the hot spring brings with it underground oils. Birds and insects are attracted to this lovely blue lake in the midst of the desert, but the polluted waters spell death, and there are several bodies lying around. The Afar collect this oily water as a skin preparation.

This was an amazing adventure, and one that I am so glad I had the opportunity to make. I don’t think that there will be any trips to the Danakil for a while, as seven days after we were there, five tourists were killed and four others taken hostage just in the camp at the base of the volcano. I count myself lucky to have been there and lucky to have got out, and incredibly sorry for those people who didn’t make it back home.